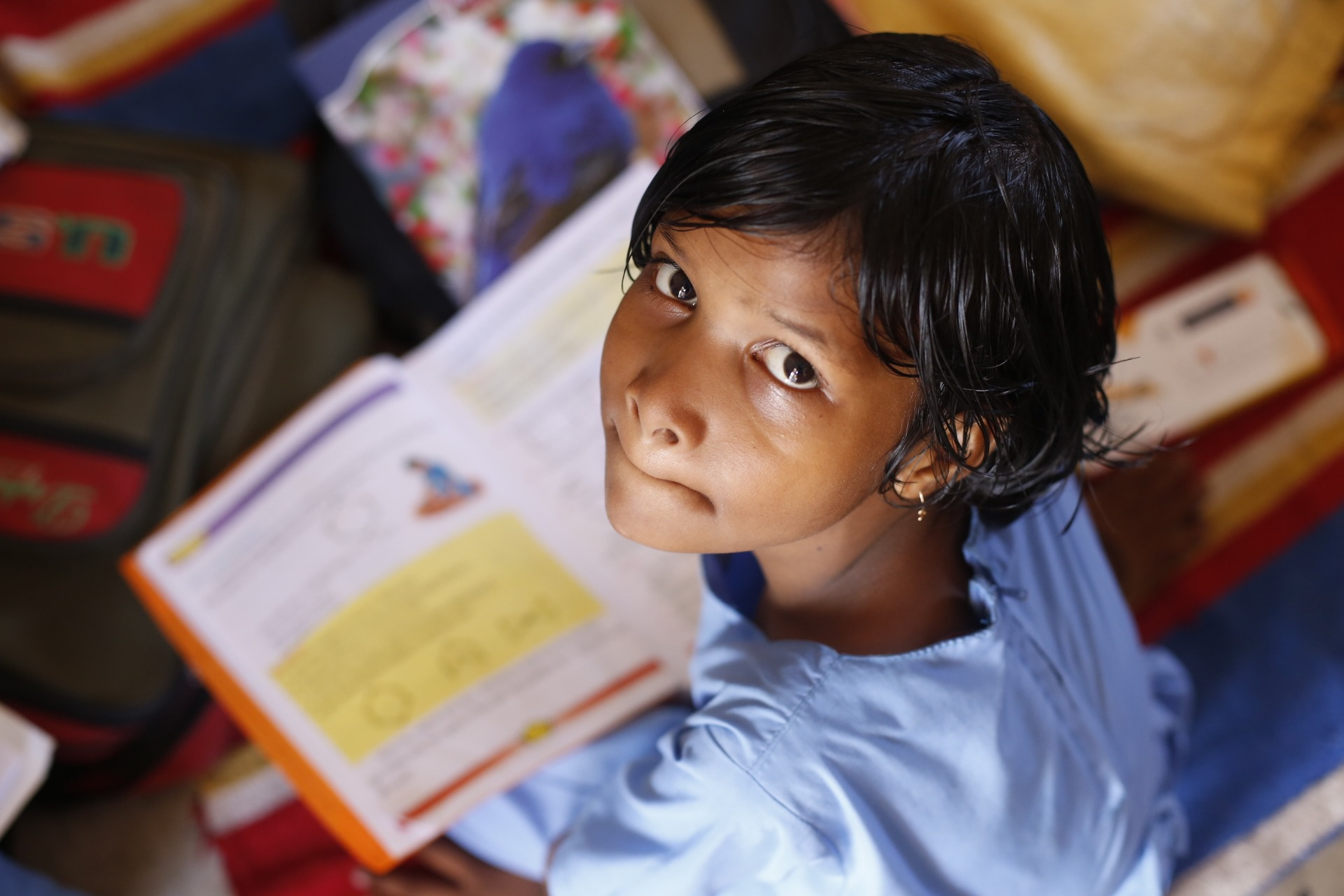

The world is adrift in the tides of hunger and desolation. It isn't easy to think about education, or anything else when your children cannot eat. And yet, the sharp attack on education during this past decade forces us to consider the future that young people will inherit.

In 2018, before the pandemic, the United Nations calculated that 258 million, or 1-in-6, school-age children were out of school. By March 2020, the start of the pandemic, UNESCO estimated that 1.5 billion children and youth were affected by school closures; a staggering 91 percent of students worldwide had their education disrupted by the lockdowns.

Whereas richer countries have returned to pre-pandemic levels of funding, in the very poorest countries funding has been driven below pre-pandemic averages. The decline in funding for education will produce a loss of nearly $21 trillion in lifetime earnings, much higher than the $17 trillion estimated in 2021.

As the economy splutters and as the owners of capital come to terms with the fact that they will not hire billions of people who become — for them — a “surplus population,” it is no wonder that the focus on education is so marginal.

Looking to the national liberation experiments of an earlier era reveals an utterly different set of values, prioritizing ending hunger, increasing literacy, and ensuring other social advances that enhanced human dignity.

From Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research comes a new series called “Studies in National Liberation.” The first study in this series, “The PAIGC’s Political Education for Liberation in Guinea-Bissau, 1963–74,” is a fabulous text based on the archival research of Sónia Vaz-Borges, a historian and the author of Militant Education, Liberation Struggle, and Consciousness: The PAIGC education in Guinea Bissau, 1963–1978 (Peter Lang, 2019).

The PAIGC, short for Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, or the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde, was founded in 1956. Like many national liberation projects, the PAIGC began within the political framework set up by the Portuguese colonial state.

The PAIGC set up a socialist project, which included an educational system that sought to abolish illiteracy and create a dignified cultural life for the population. It is this pursuit of an egalitarian educational project that attracted our attention since even in a poor country facing the armed repression of the colonial state, the PAIGC still moved precious resources away from the armed struggle to build the dignity of the people. In 1974, the country won its independence from Portugal; the values of this national liberation project continue to resonate with us today.

Until 1959, there were no secondary schools in Guinea-Bissau, which the Portuguese monarchy had controlled since 1588. In 1964, the first congress of the PAIGC, under the leadership of Amílcar Cabral, laid out the following promise to set up schools and develop teaching in all the liberated areas.

The experiences of African people, their past, their present, and their future had to be at the heart of this new education. The school curricula needed to grapple with and be shaped by the forms of knowledge that existed in local communities. - Amílcar Cabral

The study is gripping, a window into a world that has been vanquished by the International Monetary Fund’s structural adjustment austerity that has dragged Guinea-Bissau into turmoil since 1995, its literacy rate floundering near 50 percent – shocking for a country with the kind of national liberation possibilities set in motion by the PAIGC.